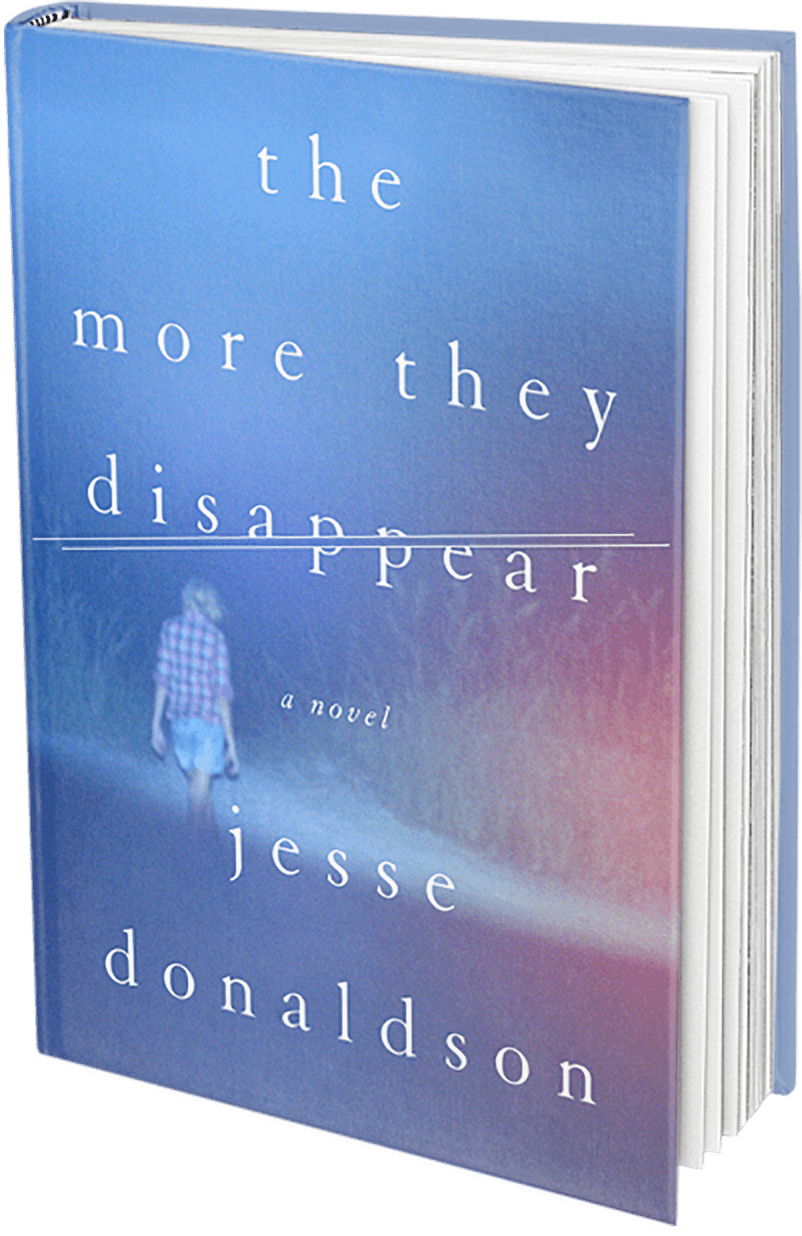

About The More They Disappear

When long-serving Kentucky sheriff Lew Mattock is murdered by a confused, drug-addicted teenager, chief deputy Harlan Dupee is tasked with solving the crime.

But as Harlan soon discovers, his former boss wasn’t exactly an innocent.

The investigation throws Harlan headlong into the burgeoning OxyContin trade, from the slanted steps of trailer parks to the manicured porches of prominent citizens, from ATV parks and tobacco farms to riverboat casinos and country clubs.

As the evidence draws him closer to his unlikely suspect, Harlan comes to question whether the law can even right a wrong during the corrupt and violent years that followed the release of OxyContin.

The More They Disappear takes us to the front lines of the battle against small-town drug abuse. It is an unnerving tale of addiction, loss, and the battle to overcome the darkest parts of ourselves.

Excerpt

Harlan kept on walking until he reached the river where he found a landing of smooth limestone and breathed deep. He felt weak and cursed himself as he clambered over the rocks upriver toward the docks of what was once the paper mill.

Under the bridge to Ohio, some ambitious tagger had spray painted a water-lapped pylon with a gigantic phallus and some indecipherable scrawl. A signature for all the world to remember. A truck rumbled across the bridge and a cluster of small stones pitched themselves over the edge and rustled the water. A fish jumped and splashed down before he could sight it. The sun had started to fall—its rays poking over the horizon like in a religious painting, like that moment right before God arrives in all his blinding glory.

Most people would say a river is something made over time, that porous, thirsty rocks slaked themselves on the rains that poured into the valley, and that the more they drank, the more they disappeared, and that before long rock gave way to water and what became Kentucky separated from what became Ohio. Others would say that some god created that river and set it there for purposes only he could divine. But Harlan, he had this image in his head of some giant, crippled god, the heel of his lame foot dragging along as he pulled himself across the earth and carved out waterways. Such a god would be easy to hunt, his path marked by that useless leg—limp like an almost dead thing. Harlan tossed a stone. Then he unzipped his pants and added to the river’s level.